India’s cooperative credit system has always carried an unusual institutional weight. It is simultaneously a local financial utility, a social trust mechanism, and—at its best—a governance instrument that converts policy intent into doorstep service. Primary Agricultural Credit Societies (PACS) sit at the centre of this architecture.

They are the last-mile face of the Short-Term Cooperative Credit Structure, but they are also increasingly being asked to become something more ambitious: multi-purpose rural service hubs that can deliver credit, inputs, and public services with the speed and auditability expected of a modern digital state.

That is the strategic logic behind the national push to computerise PACS and bring them onto a common ERP-based software platform. The objective is not merely to replace paper registers with screens. It is to re-engineer how rural credit is originated, recorded, reconciled, supervised, and diversified—so that trust is no longer dependent on personality or paperwork, but on transparent, standardised, data-backed processes.

When Prime Minister Narendra Modi inaugurated key cooperative-sector initiatives at Bharat Mandapam on February 24, 2024, he framed the cooperative modernisation agenda as a component of a much larger national transformation.

“Modernization of agricultural systems is equally important for the creation of a Viksit Bharat”, the Prime Minister said. The line matters because it links agricultural and rural institutional reform to the national development narrative: the state is not only building infrastructure; it is attempting to modernise rural institutions that intermediate finance, storage, procurement, and services.

The computerisation project is backed by a significant fiscal commitment. Parliament responses and official releases place the project outlay at ₹2,925.39 crore, with the programme designed to bring functional PACS onto a common national ERP software and link them with NABARD through State Cooperative Banks (StCBs) and District Central Cooperative Banks (DCCBs).

The same official material indicates a planned horizon up to March 31, 2027. In governance terms, this timeline is not a formality; it signals that computerisation is being treated as a multi-year institutional transition rather than a one-time procurement exercise.

What changes when PACS move to ERP? The immediate answer is accounting discipline and operational speed. Manual books create friction at every point where rural credit requires verification—membership identity, land records, legacy balances, interest calculations, repayment schedules, audit trails, and linkages with higher-tier banks.

ERP makes these processes more uniform and more legible. It can also help reduce the “trust deficit” that paper-based systems often invite—through delays, errors, and reconciliation gaps that farmers experience as arbitrariness.

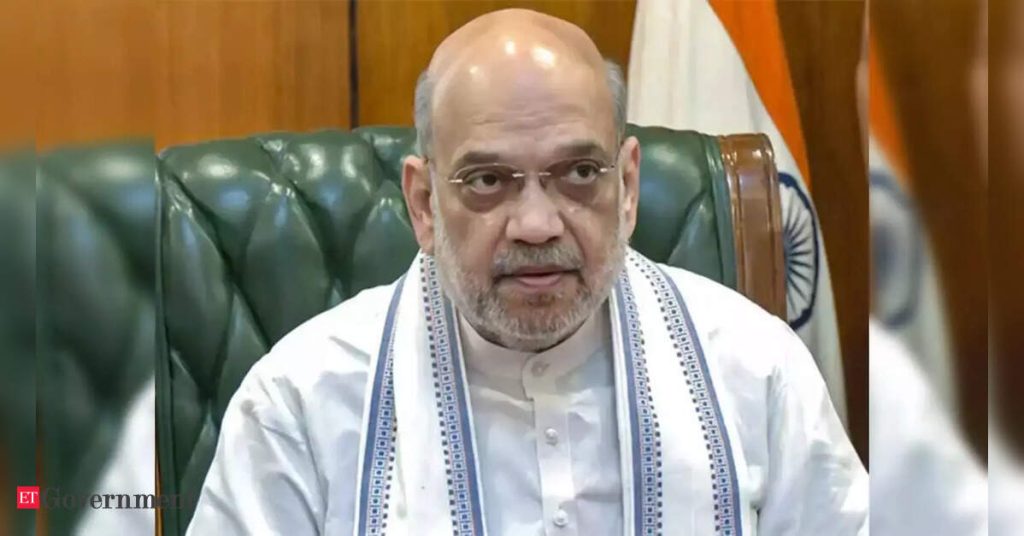

Union Minister Amit Shah has repeatedly positioned computerisation in precisely these terms: transparency, reliability, and efficiency. In an earlier articulation reported at the time of the cabinet decision on PACS computerisation, he said, “In this digital age, the decision of computerisation of PACS will increase their transparency, reliability and efficiency”.

The quote is revealing because it does not romanticise digitisation as innovation theatre; it treats it as a governance corrective for a system that must scale without losing credibility.

Yet the most consequential shift may lie beyond “faster accounting.” The common national software architecture is meant to integrate PACS into a broader cooperative grid—where transactions and records can flow upwards and sideways with minimal lag, and where policy instruments can be delivered with clearer attribution.

Parliament disclosures describe the ERP platform as capturing “all functionalities of PACS, both credit and non-credit,” and emphasise that the software can be customised for state-specific needs.That is an important design principle. Cooperatives operate under varied state laws and local realities. A usable national platform must standardise core financial logic without erasing local operational differences.

The second-order effect is service diversification. The modern PACS vision is not limited to crop loans. It extends into non-credit services that can lift rural incomes and reduce transaction costs for households: Common Service Centre (CSC)-type services, input distribution, Jan Aushadhi Kendras, storage linkages, and other community-facing functions.

Prime Minister Modi, in the same Bharat Mandapam address, explicitly pointed to the emerging multi-utility role of cooperatives and PACS—citing examples of committees functioning as Jan Aushadhi Kendras and operating PM Kisan Samruddhi Kendras. In other words, PACS are being asked to move from being primarily credit conduits to being rural service institutions with multiple revenue streams and multiple accountability lines.

Digitisation is a prerequisite for this shift, because diversified services without digital recordkeeping tend to create operational opacity. A PACS handling deposits, loans, input sales, procurement-related records, or service-fee transactions needs a unified ledger view to remain audit-ready and financially coherent.

ERP makes it possible to separate lines of business while still seeing the full institutional picture, which is essential if PACS are to become commercially viable rather than subsidy-dependent.

At scale, the programme has moved beyond the pilot stage. Official parliamentary answers in late 2025 reference expanded coverage figures—indicating that the project’s scope has been scaled to cover a larger number of PACS than initially approved, even while retaining the same outlay headline. The directional point is that this is no longer treated as an experiment; it is being framed as national rural financial infrastructure.

However, the story of digitisation is not only about capability; it is also about risk. Once PACS become digitally networked, they inherit the vulnerabilities of networked systems: credential misuse, weak device security, insider manipulation of digital workflows, ransomware risks, and data quality problems that can spread quickly if governance is lax.

ERP can reduce certain types of irregularity, but it can also create new failure modes if access controls, audit logs, and training are not treated as core—not peripheral—elements of implementation.

This makes capacity-building central. For a PACS secretary accustomed to paper ledgers, ERP is not simply a software interface; it is a new discipline of daily reconciliation, structured data entry, and time-bound closure. The success of the programme will be defined in the “last-mile routine”: whether day-end processes are actually done, whether exceptions are resolved rather than carried forward, whether reports are used for decisions rather than generated for compliance.

That is why Prime Minister Modi’s emphasis on peer learning is more than an administrative suggestion. “PACS and cooperative societies will also have to learn from each other”, he said, while recommending a portal for best practices and online training modules. In effect, he was acknowledging that technology adoption in cooperatives is as much social learning as it is IT deployment. The platform can exist, but the institutional habit of using it must be built.

The political economy dimension is equally significant. Digitisation can rebalance power inside rural credit ecosystems. When records are standardised and auditable, discretion narrows. When transactions are time-stamped and reconciled, informal “adjustments” become harder.

When reporting is real-time or near-real-time, supervisory institutions can detect anomalies earlier. Parliament responses describing expected outcomes explicitly include faster functioning in a “transparent manner” and prevention of financial irregularities, alongside improved facilities and enhanced financial inclusion. These are not small gains; they strike at the root of why many rural borrowers historically oscillate between trust and suspicion in local institutions.

At the same time, digitisation should not be confused with automatic inclusion. Inclusion requires last-mile connectivity, device reliability, and human support. Many PACS operate in regions where network conditions are uneven and digital literacy varies. The programme therefore succeeds only if infrastructure procurement is paired with ongoing technical support, local-language interfaces, and a realistic approach to transitional hybrid workflows. National standardisation must be compatible with rural variability.

There is also a longer-term governance opportunity embedded in the architecture: better data, better policy. Once PACS records become structured, policymakers can see patterns in credit demand, repayment stress, seasonal needs, and service uptake with far greater clarity—provided data governance is designed responsibly.

This can improve risk management, target support to distressed regions, and evaluate the effectiveness of interest subvention or other schemes in practice. But it requires strong safeguards: clear purpose limitation, role-based access, and controls that ensure that farmer data is not exploited or mishandled.

Viewed in this light, computerisation is not simply a cooperative-sector reform. It is a rural state-capacity project. It attempts to strengthen an institution that already exists in thousands of villages, rather than building a new last-mile bureaucracy from scratch. If executed with discipline, PACS can become the connective tissue between banks, farmers, service platforms, and welfare systems—providing the kind of grounded, transaction-level capability that modern governance increasingly depends on.

The deeper wager is that a cooperative, once digitised, can combine the legitimacy of community institutions with the efficiency of digital systems. That is the essence of what “Sahakar se Samriddhi” is trying to operationalise: prosperity through cooperation, enabled by technology, and validated by transparency.

The outcome will not be measured by how many devices were delivered or how many logins were created. It will be measured by whether a farmer experiences faster service, clearer records, fewer disputes, and more reliable access—whether for credit, inputs, storage, or essential services—through a PACS that finally functions like a modern institution rather than a paper-bound relic.