Authors

Dr Raul Villamarin Rodriguez & Dr Hemachandran K

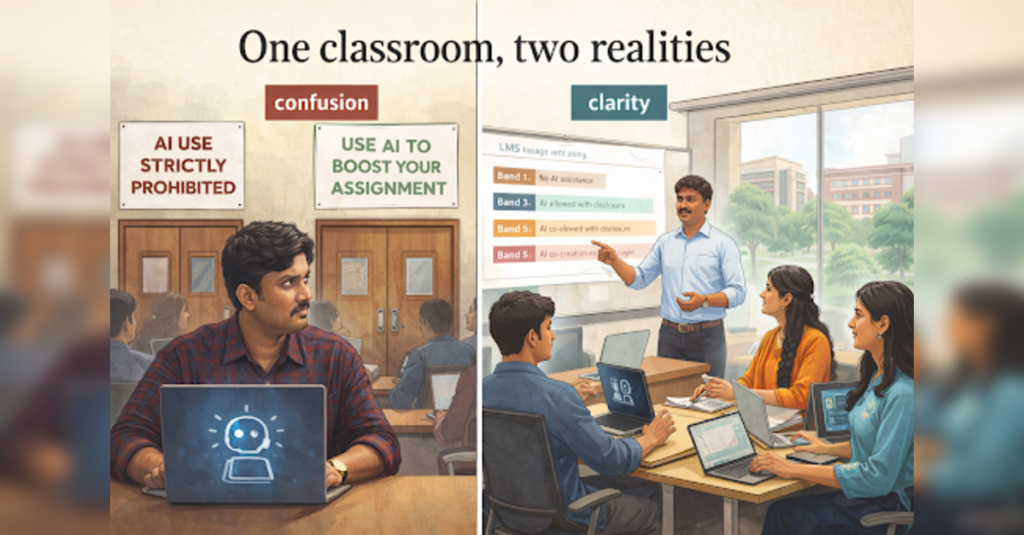

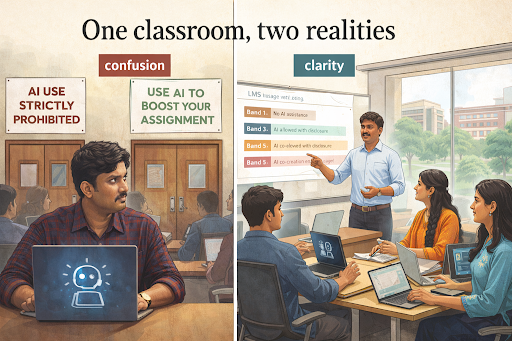

Across Indian campuses, a quiet contradiction is playing out every day. A student uses the same generative AI tool in two different courses. In a marketing class, she is applauded for “smartly leveraging technology” to shape campaign ideas. In a law elective, the same week, she is formally warned for “misusing AI” after running her draft through a chatbot to tidy the language. The tool is the same. Her intention is similar. But the rules, as she experiences them, depend entirely on which classroom door she walks through.

AI policies are not yet teaching our classes

Over the past two years, Indian higher education has moved at impressive speed on AI. More than half of higher education institutions now report having some form of AI-related policy, and over 60% permit the use of AI tools by students in at least some contexts. Yet in our work with faculty and students, both at Woxsen University and beyond, we see a persistent gap between policy on paper and practice in classrooms.

Students describe “policy by professor”: what is considered legitimate AI support in one course is treated as academic misconduct in another, even within the same programme or semester. Faculty, especially those under pressure to “do something” about AI, oscillate between enthusiastic experimentation and outright bans. Institutional leaders announce “AI-ready campuses” in brochures, while internal emails reveal intense confusion about what is actually allowed.

For rectors, vice-chancellors, and deans, this is not a marginal issue. As generative AI permeates assessment, feedback, and administrative workflows, the credibility of an institution’s AI stance will be judged not by a PDF on its website, but by the consistency students and faculty feel in their daily practice.

The real cost of “policy by professor”

The first cost is confusion. Students today understand that AI is everywhere—inside learning platforms, plagiarism checkers, writing tools and search engines. What they do not understand is when the use of a public model is considered formative support and when it becomes a punishable shortcut. When the same AI action is praised in one course and penalised in another, we are not teaching academic integrity; we are teaching unpredictability.

The second cost is inequity. Students who are confident and well-networked quietly negotiate AI expectations with each instructor. Others—often first-generation learners or those from less resourced colleges—avoid AI entirely out of fear, even when appropriate use could significantly enhance their learning. This creates a new divide between AI-fluent and AI-anxious graduates, layered on top of existing inequalities in language, digital access, and social capital.

The third cost is reputational and strategic. As Indian universities position themselves as AI-enabled and future-ready, employers, accreditors, and international partners are asking sharper questions. They want evidence that AI in teaching and assessment is governed, auditable, and reasonably consistent across the institution—not left to chance or to individual comfort levels.

From principle to practice: making AI rules visible

The good news is that closing this policy–practice gap does not require another 50-page guideline. It requires a simple grammar for AI use that is visible wherever teaching and learning actually happen—on the LMS, in syllabi, in assignment briefs, and in viva rooms.

One practical route, aligned with global practice, is to define a small set of “usage bands” or levels of AI involvement. Internationally, we have seen universities use three- to five-level schemes that move from “No AI assistance permitted” to “AI allowed for specific, declared tasks” to “AI co-creation encouraged, with the student responsible for verification and reflection.” The exact labels can vary, but the principle is constant: every assessment, in every programme, carries a clear AI-use designation.

At Woxsen, our own AI Assessment Policy (AIAP) framework moves in this direction by defining levels of acceptable AI involvement, from minimal support to high levels of collaboration with AI systems, always under human accountability. That kind of structure allows faculty to choose the right level for each task while giving students a coherent vocabulary across courses. The crucial step is to lift this vocabulary out of internal documents and embed it into the artefacts students actually see.

What Indian universities can do in the next semester

For institutional leaders, 2026 offers an opportunity to translate intent into practice. Four concrete moves can be implemented in the coming academic cycle.

1. Put AI clarity into every syllabus template

From 2026–27 onwards, every course outline should contain a short, standardised AI-use section in plain language: which tools are permitted, for what types of tasks, at which usage band, with what disclosure expectations. Academic offices can provide pre-approved statements for each usage band, allowing faculty to select and lightly adapt rather than draft from scratch. Quality assurance teams should treat an empty AI section as seriously as a missing assessment rubric.

2. Label every major assessment with an AI band

Assignments already specify word counts, deadlines, and weightage. They should also specify an AI band: “Band 1 – No AI assistance”, “Band 3 – AI permitted for brainstorming and structure, disclosure required”, “Band 5 – AI co-creation encouraged; student must explain and defend outputs.” These labels must appear consistently on the LMS, in assignment PDFs, and on exam notices. Over time, the pattern of labels will reveal where AI is being meaningfully integrated and where further support or redesign is needed.

3. Redesign at least one key assessment per programme for an AI-present world

Not every course can be redesigned at once, and faculty fatigue is real. A realistic goal is that each programme identifies one or two core assessments this year to rework with explicit AI assumptions: for instance, requiring students to use AI at a specified band and then critically reflect on its limitations, or combining AI-generated drafts with in-person oral defence or problem-solving. This shifts the conversation from “How do we catch AI?” to “How do we teach with AI and still assess human understanding?”

4. Train faculty for judgement, not just compliance

Policies can set boundaries, but only faculty judgement can interpret complex cases. Short, discipline-specific workshops can walk staff through real scenarios—AI use for grammar only, AI-written code without comprehension, AI-generated personas for business projects—and ask: at which band does this fall? What is acceptable, what is problematic, and how should it be handled under our policy? The goal is to build a shared culture of decision-making, so that a student moving from engineering to management encounters different content, but not entirely different moral universes.

Indian higher education is at an inflection point. In 2025, institutions proved they could move quickly to adopt AI tools and draft AI policies. In 2026, the test is whether those policies can actually teach—whether a student navigating multiple classrooms experiences AI as a coherent, explainable part of their education rather than a game of regulatory roulette. Universities that close the policy–practice gap will not only reduce conflict and anxiety; they will graduate a generation of professionals who understand, through lived experience, what responsible AI looks like in practice.

Dr Raul Villamarin Rodriguez is the Vice President, Woxsen University, Hyderabad, India. Dr Hemachandran K is the Director, AI Research Centre & Vice Dean, School of Business, Woxsen University, Hyderabad, India.

DISCLAIMER: The views expressed are solely of the author and ETEDUCATION does not necessarily subscribe to it. ETEDUCATION will not be responsible for any damage caused to any person or organisation directly or indirectly.